Even the man of purest motives, if he speaks unclearly, cannot be trusted. There is nothing to trust.

- unknown

In Part 1, I aimed to assemble a practical theory of meaning that answered two questions: “First, given some word, how can we figure out its meaning? Second, given some word and its meaning, how can this be put into a definition?” Now, I will focus on building out a single, usable answer to these questions.

The Nature of Meaning

I have settled on the following account: within a language, a term’s meaning is the set of ideas it can be relied upon to convey. If a term’s meaning changes, it can be relied upon to convey ideas to a different extent. If two terms can be relied upon to convey ideas to different extents, they have different meanings.

This account immediately demands a more precise elaboration of the meanings of the terms used. Here, a language is some stipulated mapping between terms and sets of ideas. A term is any symbol or combination of symbols to which a set of ideas can be assigned. An idea is a mental object such as a sensation, memory, notion, image, relation, or some combination thereof – anything which can, in the colloquial sense, be “thought about.” Lastly, for an idea to be conveyed, is for it to be generated in the mind of the person interpreting the term, as a result of their attempt to interpret.

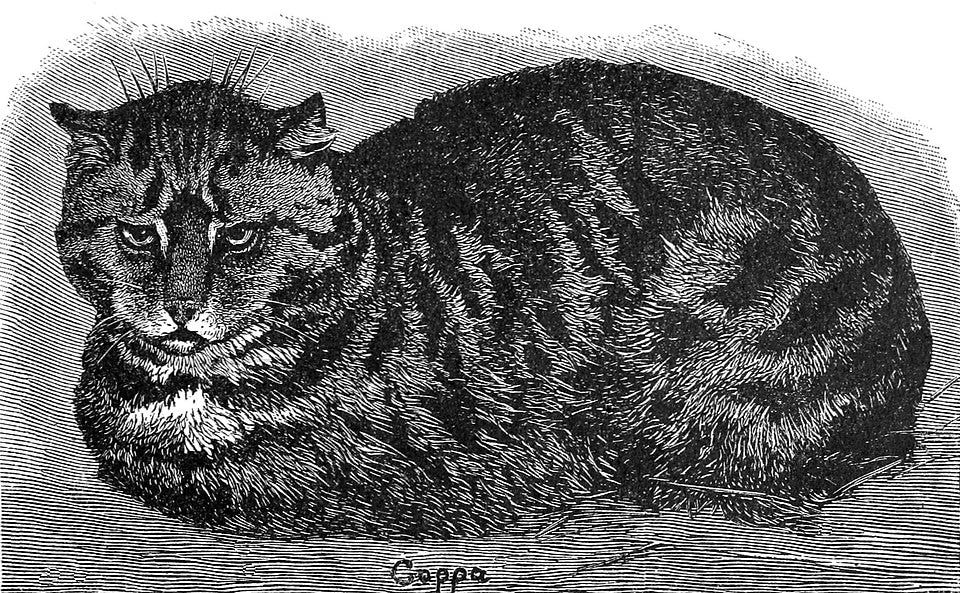

Whether a term conveys a set of ideas reliably depends on the extent to which two speakers have the same understanding of their language. Within a language are many sub-languages – “dialects.” Dialects might, in turn, have sub-dialects, and further subdivisions down toward the per-individual level. Different dialects can stipulate different meanings for terms – in technical dialects, for instance, “cat” might mean “any member of the Felidae family”, while in a colloquial dialect “cat” refers to pet cats but might generally be presumed to exclude lions and cougars without further specification.

By my lights, this account can be harmonized with much of the existing literature in semantics – on Wittgenstein’s account (“meaning is use”), for instance, it is the set of ideas a term can be relied upon to convey that determines the term’s use(s) in any given language-game. For Carnap, the process of conceptual engineering is an attempt to rigorously define the set of ideas a term conveys, and to make tweaks that increase the reliability with which it does this. Per Putnam, the set of ideas a term can be relied upon to convey “just ain’t in the head!” – rather, the ideas subsequently conveyed are. Per Frege, the set of ideas a term can be relied upon to convey isn’t the set of things the term refers to (its reference) – rather, the set of ideas a term can be relied upon to convey determines reference, as Frege demanded his “sense” must.

The Meaning of Meaning

One of the surest tests of a philosophical theory (and particularly a theory of language), is to apply it to itself. Previously I have emphasized the importance of disambiguating between the definition of a term versus the facts about the thing to which the term refers.1 For some term X, we can offer an account of the meaning of X, and an account of the nature of X, and the line between the two must be unblurred. It is absolutely vital that the account of the nature of meaning that I’m proposing – “within a language, a term’s meaning is the set of ideas it can be relied upon to convey” – is not a definition of “meaning.” It is a claim about meanings – I am saying, this is generally true of meanings, and if there is a meaning which doesn’t fit this characterization, my claim is simply incorrect.

So, then, let’s apply this practical theory of meaning to the term “meaning” itself:

“First, given some word, how can we figure out its meaning?” We must look to the set of ideas the word “meaning” can be relied upon to convey within this language and dialect. We can consider basic, uncontroversial premises that both a speaker and interpreter would assume, when it comes to meanings – “meanings are properties of terms,” for instance. Consider the significance of a potential counterexample - if a thing is not a property of a term, we’re simply not using the term “meaning” to refer to it. A meaning is a thing that a definition seeks to describe. The meaning of a term determines what it refers to, and affects the truth of statements that include the term.

“Second, given some word and its meaning, how can this be put into a definition?” We want a phrase that captures and summarizes the set of ideas that the word “meaning” can be relied upon to convey. Ideally, this phrase could itself be relied upon to convey the exact same ideas – it would be exactly synonymous with the term, a perfect definition – but this is not obviously possible, in the dialect we are using, without extensively engineering the concept of meaning. And there is only so much time in the day. Compiling the above claims, and trimming for the sake of clarity, yields the following definition: a meaning is a property of a term that determines what it refers to. This activity – determining what a term refers to – is essential to meaning.

This definition can be substituted into the earlier account, in lieu of the defined term: “within a language, the property of a term that determines what it refers to is the set of ideas it can be relied upon to convey.” We can now offer an account of the nature of meaning, use this account to build a definition that captures the meaning of meaning, and, in the process, illustrate the difference between the two.

Next Steps

I have begun this blog with an extensive treatment of semantics, and justified it in part by laying out a coarse “order of operations” for philosophical inquiry:

Any answer to an ethical or political question is a claim, which requires us to consider its truth. And to consider the truth of a claim, one must first know what it means.2

We encounter a bootstrap problem, however – after all, any answer to a semantic question (including the one we have just developed) is a claim, which requires us to consider its truth. But to consider the truth of the above claim, we must assemble a practical theory of epistemology – but to assemble a practical theory of epistemology, we must, at least for now, rely on the above claim. This predicament arises in any attempt to do philosophy “from scratch” – the only starting point which is ever fully proper, for philosophical inquiry, is wherever one happens to be when they start doing philosophy.

In any case, I am done with semantics for now. Future articles will be published with the goal in mind (among other topics) of developing a practical theory of epistemology.

A personal note: I must apologize for the gap in time between this article and the previous one, however, I have been fairly preoccupied over the past few weeks – I got married, and returned from my honeymoon last weekend. I have been meaning to get back to this, and now have the opportunity.

Lastly, a word of advice – sharpen your knives! Not a metaphor – the ones in your kitchen, I recommend you sharpen them. Sharp knives will dramatically improve your quality of life. And don’t make ceviche with freshwater fish!

Misuses of Meaning

A warm beer is better than a cold beer. After all, a warm beer is better than nothing, and nothing is better than a cold beer.