An Attorney's Guide to Semantics

Or in other words: How to Mean What You Say

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description, and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.

- U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, on the meaning of “hard-core pornography.”

Much of the need for attorneys arises from semantic confusion. In a world where everyone spoke and understood each other perfectly clearly, legislators could write laws that perfectly communicated which conduct was to be rewarded or punished in which manner. The constitution would perfectly communicate which laws are not to be enforced. Police officers, bailiffs, soldiers, and so on – the arms of the law – could then enforce the enforceable ones in the precise manner specified. There’d be no confusion as to whether a thing is legal, constitutional, contractually required, and so on. In this sense, then, much of an attorney’s work is “semantic labor.”

An attorney needs a working theory of meaning in the same way a plumber needs a working theory of hydrodynamics. And attorneys rely on many working theories that follow directly from philosophical inquiry – working theories of epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and so on. The same goes for anyone who spends enough time writing, reading, or, God forbid, blogging on Substack. Future articles will touch on these other areas of inquiry as well, but as I see it, theories of meaning are a proper first step. Any answer to an ethical or political question is a claim, which requires us to consider its truth. And to consider the truth of a claim, one must first know what it means.

Last week’s article examined “substantive definition,” a particular misstep that can happen when defining terms, where a word is given a definition removed from its ordinary meaning – the effect of this is to get “one fact for free”, by disguising a substantive claim as a linguistic choice. Semantic missteps of this sort can be costly – they can weaken a theory’s ability to explain, make it less persuasive, or generate lengthy debates that need never have existed in the first place.

Misuses of Meaning

A warm beer is better than a cold beer. After all, a warm beer is better than nothing, and nothing is better than a cold beer.

But to avoid missteps like substantive definition, we need to assemble a practical theory of meaning. Of course, doing this from scratch is unnecessary, and well beyond the scope of a blog post in any case. Nor am I especially well-equipped to do so, as I am not a professional philosopher. Fortunately, there is a wealth of existing books and papers on the topic. Especially among analytic philosophers, when it comes to semantics, enough ink has been spilled to make a squid blush. The goal for this working theory is to offer sensible, useful answers to two questions: First, given some word, how can we figure out its meaning? Second, given some word and its meaning, how can this be put into a definition? There are a few other questions that will be relevant along the way – what are meanings? Where do they come from? What do they do, exactly? Once we have workable answers to these questions, future articles will begin to connect our notions of meaning to notions of truth.

I. What Meanings Aren’t

A favorite topic in the philosophy of semantics is discussion of what meanings aren’t. Most (if not all) landmark works in semantics touch on this theme.

A. Definitions

As I discussed in my last article, there is such a thing as a “bad definition.” A bad definition is one which does not match a word’s meaning. Naturally, this presumes that the definition is not itself the word’s meaning. But is this a safe assumption?

I think so - or at least, I think it is the case. First off, many words do not have clear definitions. It is entirely possible to grasp the meanings of the words “round,” “orange,” “loud,” “difficult,” “lumpy,” and “long,” at least in the colloquial sense, without writing out some definition. Only when the meaning of a word is disputed or unknown does a written definition become useful – and the meanings of these terms are rarely in dispute. These meanings are learned in childhood, perhaps through picture books.

Second, the idea that meanings are definitions is just not compatible with what definitions do. Definitions capture meanings – they are an effort to put a word’s meaning into words. They do this to better and worse extents. A definition is sort of a picture of a word’s meaning, in this sense – we consider the meanings of the words in the definition, and get an idea of the defined word’s meaning by assembling these. Quine puts it quite well:

The lexicographer is an empirical scientist, whose business is the recording of antecedent facts; and if he glosses 'bachelor' as 'unmarried man' it is because of his belief that there is a relation of synonymy between these forms, implicit in general or preferred usage prior to his own work. The notion of synonymy presupposed here has still to be clarified, presumably in terms relating to linguistic behavior. Certainly the "definition" which is the lexicographer's report of an observed synonymy cannot be taken as the ground of the synonymy.

A definition, then, explains a meaning, but is not the meaning itself. It is a mistake for an English speaker to define “cat” as “hand grenade,” not merely because there is a risk of confusion (and danger!) if the word is used that way, but because it is incorrect – “hand grenade” itself has a meaning which simply does not match.

B. Reference/Extension

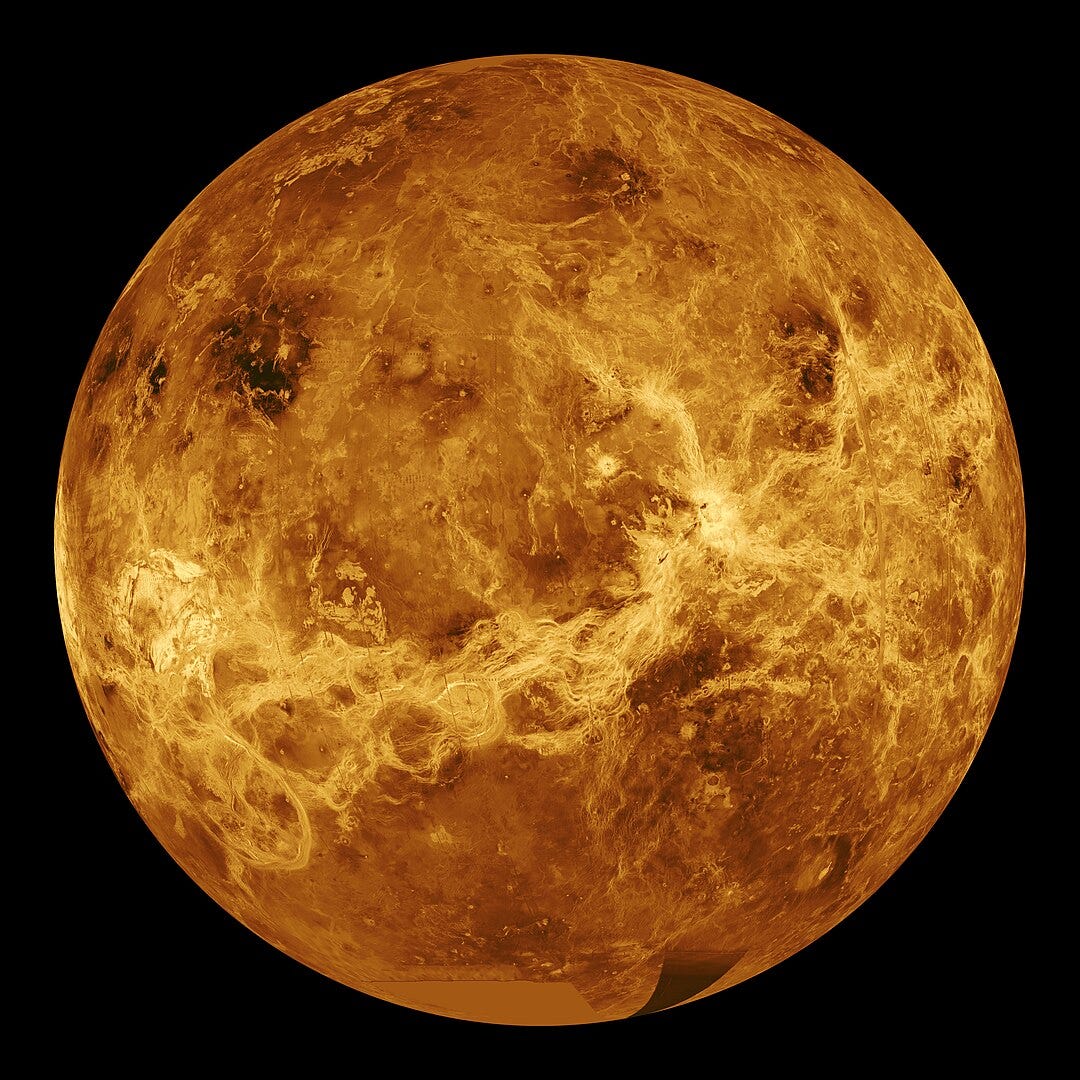

Each word has an extension – the set of things in the universe to which the word refers. The extension of “dog”, for instance, is the set of all actually existent dogs in the world. Although a word’s meaning determines its extension (and a word’s extension is evidence of its meaning), they are not the same thing. Frege’s paper Sense and Reference made this point with the famous example of the phrases “the morning star” and “the evening star” – both refer to Venus, but their meaning is different.

There is a word, and there is the thing the word refers to, but there is a third thing – what Frege calls the word’s “sense.” Another classic example is “Superman” and “Clark Kent.” A person unaware of Superman’s secret identity might know the sense of each name without knowing that their reference is shared, and use them in conversation to mean very different things. Likewise for “Emmanuel Macron” and “the President of France” – identical extensions (currently), but different meanings. As on the issue of substantive definition, it is crucial here to distinguish between the meaning of a word, and the facts about the thing to which the word refers – “Emmanuel Macron is the President of France” is hardly true by definition!

II. What Meanings Might Be

In arguing that the claim “Emmanuel Macron is the President of France” is not true by definition, we might point out that it is conceivable for the President of France to be someone other than him, without the meaning of the words changing. But what if two terms point to the exact same thing in all possible worlds – could they still mean different things?

A. Carnap – Analyzing Meaning as Intension

A word’s intension determines its extension in all possible worlds. It certainly seems that two words with identical intensions have the same meaning – after all, there would be no thing in any possible world which could be referred to with one word, but not the other.1 Regardless of whether meanings and intensions are exactly the same thing, it does seem that facts about meanings determine and explain facts about intension, while facts about intension are good evidence of a word’s meaning.

This is, roughly, the view Rudolf Carnap laid out in his 1947 book Meaning and Necessity. Carnap fleshed out a “method of extension and intension” to be used for analyzing meanings. For Carnap, to analyze a word’s meaning is to analyze its intension. The intension of a “predicator” – a word which sets out some class of qualifying objects, including most nouns and adjectives, like “human,” “elephant,” “large,” and so on – is the property (or set of properties) expressed. The intension of an individual expression (which refers to an individual, like Gumphus, or Emmanuel Macron) is an “individual concept.” For Carnap, these properties and individual concepts are collectively referred to as concepts:

For this term it is especially important to stress the fact that it is not to be understood in a mental sense, that is, as referring to a process of imagining, thinking, conceiving, or the like, but rather to something objective that is found in nature and that is expressed in language by a designator of nonsentential form. (This does not, of course, preclude the possibility that a concept – for example, a property objectively possessed by a given thing – may be subjectively perceived, compared, thought about, etc.).2

In Carnap’s account, then, concepts are objective non-mental things that words in a language point at. A word’s extension and intension are analogous to what Frege considered its reference and sense, respectively. When examining a word’s meaning, one looks to its use as evidence of its extension; one looks at its extension as evidence of its intension; and one analyzes the intension to understand the concept that the word is expressing.

Carnap offers a methodology that answers our first question of how to determine a word’s meaning. What does “dog” mean? First, gather data about the set of all things we call dogs. Based on the common properties of the things in this set, theorize about the set of all existent things we would call dogs. Refine this set of properties by imagining hypothetical dog-candidates – what if there was a thing which looked and barked like a dog, but was made entirely of cheese on the inside? Would it make sense to call that a dog? The end result of the analysis is the set of properties that makes a thing a dog – its necessary and sufficient conditions. Where these boundaries cannot be cleanly delineated, due to ambiguities and inconsistencies in a word’s use, Carnap prescribes a process of “explication,” in which refinements to a word’s meaning are proposed to make it more rigorous and clear.

Carnap offers an answer to our second question, as well – given some word and knowledge of its meaning, a word can be defined by describing the properties it expresses. Listing a word’s necessary and sufficient conditions is adequate, on this account, to explain its meaning. And this appears to work in many formal cases. “A bachelor is an unmarried man” does exactly this – “unmarried” and “man” are two conditions, both of which are necessary (there are no bachelors who are unmarried) and, together, sufficient (there is no one who is both unmarried and a man, but not a bachelor). A word which points to an individual (such as a name) expresses a concept of all the things in all possible worlds that would qualify as “that person.”

Carnap’s framework is undoubtedly an achievement. His writing is rigorous and precise, to a fault – he transforms semantic analysis into a sort of baffling, magical algebra:

He offers a serious contender in our search for a “semantic artisan’s” working theory of meaning. His approach sets the standard for much subsequent work on semantics - though much of it is critical.

B. Wittgenstein – Meaning as Use

Probably the most famous philosopher of language, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations offered a very different account of meaning in 1953. In Wittgenstein’s account, meaning is a much mushier thing than intension. There is far less math here. Wittgenstein points out that, if we are taking the way a word is used as evidence of its extension, intension, and/or sense – “doesn’t the fact that sentences have the same sense consist in their having the same use?”

Wittgenstein compares the words in a language to tools in a toolbox. Just as each tool in a toolbox has its function, each word has its use – and this is what one need consider to offer an account of the words’ meanings:

Think of the tools in a tool-box: there is a hammer, pliers, a saw, a screw-driver, a rule, a glue-pot, glue, nails and screws – The functions of words are as diverse as the functions of these objects.

[***]

For a large class of cases – though not for all – in which we employ the word “meaning” it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.3 And the meaning of a name is sometimes explained by pointing to its bearer.4

On this account, a word’s meaning is its function within one or more “language-games” – and in different language games, a word can have different meanings. Wittgenstein also stresses that, for most words, it is simply impossible to offer a rigorous definition in terms of necessary and sufficient conditions – he gives the word “game” as an example. Rather than some rigid set of criteria, games have a “family resemblance” – lots of games have common features, but there is no set of features that all games must have, or that automatically qualifies a thing as a “game.”

This framework offers an answer to our first practical question. To ascertain a word’s meaning, we infer its role in a language game by looking at the manner in which it is used. We must make a careful distinction here. A word’s “use” in this sense is its role or function within a language game. The way a word is, as a matter of fact, used is not quite the same thing as its use – rather, the former is the evidence from which conclusions about the latter are to be drawn. The goal is to figure out the rules of the game by watching people play it, and a word’s function within the game is determined by the rules. A person could misuse a word, and this would not in and of itself modify the word’s meaning (unless it somehow modified the game) – rather, this person is just playing the language-game that they are in poorly.

This theory offers an answer to our second question as well – given a word, and knowledge of its use in a language-game, we define the word by offering an account of the role it plays in that language game. This requires an explanation of what the “game” is, if that cannot be gleaned from context. For a word which gathers its meaning from a “family resemblance,” one might offer an account of its meaning by pointing to exemplars, or features which are typical (albeit not ubiquitous). It is much easier to offer a definition of “dog” using this method, than by listing some set of necessary and sufficient features.

III. Conclusion

Thus far we have two contenders for a theory of meaning. Both are quite old and there is much more ground to cover. It feels pointless, and sort of cheap, to offer a list of “pros and cons” between Carnap’s and Wittgenstein’s theories. In a sense, they are seeking to answer different questions: Wittgenstein wants an account of language as it exists, presently, in the world, while Carnap wants an account of what language could be made into, if only we spoke more clearly. Carnap also seems to prioritize claims (what he calls ‘declarative sentences’) – for him, the difference in meaning between the word “water” and the sentence “Water!” is irrelevant, or at least, beyond the scope of his project. Carnap’s system sets out a methodology one might employ to engage in “conceptual engineering” – but also seems to require one to engage in a great deal of conceptual engineering before his system is of much use. Wittgenstein more takes language “where it’s at” – but, while this might be more useful to lawyers, it provides little direction (that I could glean) on “where to go,” which is to say, how to build our language games, and how to tweak them to make them easier or more productive to play.

The next installment in this series will survey later developments. Frankly, this may take more than a week, as there is much required reading, and most of it I have not yet done. Please be sure to subscribe, so that you do not miss it. If you have made it all the way to the end of this article, chances are, you will appreciate future posts.

A personal note: this weekend, I made buttermilk crepes using this recipe. I cannot recommend them enough - they brought me great joy. I wish I had taken a photo. The recipe (or rather, the small essay which precedes every recipe on the internet, for some reason) had a curious bit of wisdom:

There is a saying in Russian "Первый блин комом," which means "the first crepe (or pancake) is always lumpy (or broken)." This is used as a metaphor for lots of things in life, but is so true for cooking crepes!

(emphasis in original). I find this compelling. In this sense, these posts on this blog are my “first crepes” – they may be lumpy. This one, for instance, is perhaps too long, perhaps too dry. But I have already spent too much time editing it. -G.

EDIT: Part 2 has been released! You can find it here:

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s article on intensional logic uses the terms “meaning” and “intension” interchangeably.

Carnap, Meaning and Necessity (1947), p. 21.

Wittgenstein says that this is how meaning can be “defined.” Ask yourself - is this a substantive definition? Does “use” truly capture the meaning of “meaning”? Is “use” meaning’s use?

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (1953), §§ 11, 43.

Thanks. Very interesting work. Keep it up.

You sketch a meaning of concept that serves well in the context of linguistics, but differs from my own sense of a "concept" as a neural model in someone's brain that also needs to be pinned down in terms of its extension, intension, and so on. For instance, to pick a contentious example, human brains have a concept of redness that arguably fails to pick out anything real in the world, and it is important to be able to talk about that concept without reference to whether it is backed up by a real-world property.

What word would you suggest for the neural model (of redness, or consciousness, or a dog) that would not clash with the meaning of "concept" in your article? The word "model" seems to have the wrong connotations, as it suggests a toy version with working parts; the word "idea" seems too loose, and so on.

Oh!, I have a good one on Semantics:

https://substack.com/@federicosotodelalba/note/c-107322166