A Partial Defense of Singerism Against its Worthy Adversaries

On the Sublime Art of Bullet-Biting

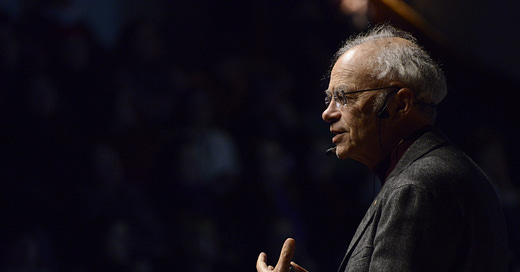

Bo Winegard’s yesterday-published article in Aporia, Against Singerism, makes the case that three philosophical commitments of Peter Singer (utilitarianism, cosmopolitanism, and rationalism) are, generally, “spectacularly wrong.” As I am quite partial to utilitarianism (in some formulations), I figured I’d take a stab at responding to his arguments on that point. I’m partial to cosmopolitanism and rationalism as well, but less familiar with the literature on those points.

Winegard opens: the “rot” at the center of utilitarianism “is its core premise that pleasure and pain are intrinsically good and bad, rather than contextually or relationally so.” He offers two examples – first:

For example, on a strict hedonistic view, we should not desire or morally approve of the suffering of depraved rapists, if that suffering has no deterrent or rehabilitative effect. But common sense suggests otherwise.

It’s certainly intuitive that it’s good to punish people who do bad things, doubtless including depraved rape – but one must establish that this intuition is not derived substantially, if not entirely, from the deterrent and rehabilitative effect of punishment.

This forecasts an issue which is endemic to critiques of utilitarianism, in Winegard’s article and elsewhere: what I will call an empty bullet.1 Suppose you offer a substantive theoretical claim, for instance, “objects fall because things with mass are attracted to each other.” A person may seek to rebut this claim by offering the following thought experiment:

If you released an elephant with no mass from the top of a skyscraper, it would not fall. But this is absurd, because it is extremely intuitive that elephants always fall. It is just common sense – your intuitions on this issue, and mine, are ironclad. Thus, your theory must be mistaken.

It certainly is intuitive that elephants always fall. Conceding that an elephant might not fall if released from the top of a skyscraper, might seem like quite a bullet to bite! The notion is absurd!

But the bullet is empty! Our intuitions rest on the actual facts about elephants, including, crucially, that they have mass. If we consider this, the fact that a theory yields counterintuitive conclusions when applied to a counterintuitive case is not especially damning evidence against the theory – and it is a mistake to treat it as such.

Likewise, here, our intuitions regarding what rapists deserve rest on the belief that, in the long term, punishing rape reliably and foreseeably leads to good outcomes. I believe this is a fact about the world, and I’d go so far as to say I’m not aware of a single exception. The alternative is astoundingly counterintuitive. Applying utilitarianism to a gerrymandered case where we stipulate that no deterrence could possibly result from a given punishment, or any other long-term positive consequence, and somehow that this is knowable with certainty, yields a counterintuitive conclusion. This should come as no surprise!

If there are contingent reasons why we should punish, eliminating those reasons will always yield a possible case where we shouldn’t punish! And this is true for any theory, except those which say either that punishment is warranted for no reason, or that the appropriateness of punishment is a logical necessity. And (by my lights) neither makes much sense!

Winegard offers a second example:

Consider an individual who derives pleasure from watching animated child pornography or from observing children cry on a playground. Even if this behavior results in no additional suffering in the world, many would judge such pleasures to be morally perverse.

This is another empty bullet – look at the “if”! It is highly intuitive that, if a person enjoys watching children be harmed, one might reasonably anticipate that they may go on to harm children, or at a minimum, that their risk of doing so substantially increases. This is very reliably the case, and I think intuitively, most presume it as a matter of principle. It’s certainly why I disapprove of people deriving pleasure from harm to children. The hypothetical requires that we suppose there is someone who tends to enjoy seeing children harmed, but we somehow know with certainty all future courses of action they will take and have perfect certainty that none will result in harm to children. This has never, in history, been a belief that we would be justified in having about a person. The case is not a logical impossibility – but it is certainly counterintuitive! Is there any surprise it leads us to counterintuitive conclusions?

The Internal Critique

Next, Winegard offers a more complex internal critique, after setting up four premises:

Pleasure and pain are intrinsically good and bad. Hence, pleasure should be maximized, and pain minimized.

Human behavior significantly affects the pleasure and pain of others. For instance, being kind to a waiter may bring him joy; being rude may cause anger or distress.

Pleasure and pain play causal roles in motivating behavior. The pleasure of being admired may inspire someone to become a doctor; fear of punishment may deter someone from committing violence.

Some individuals have greater capacity to produce pleasure or reduce pain than others. A charismatic actor beloved by millions may raise global happiness far more than an unknown, unskilled individual ever could.

[A] consistent utilitarian cannot be impartial about persons, only about utility. Since some individuals generate far more utility than others, their interests must matter more. Thus, the supposed impartiality of utilitarianism collapses into a covert form of moral elitism. Persons are to be valued not as ends, but as instruments of aggregate utility. The famous actor, the brilliant musician, the genius doctor should be treated better than the ordinary farmer or the middling painter.

The difficult part here is the third premise – “pleasure and pain play causal roles in motivating behavior.” It does not obviously follow from this that the interests of people who are better-equipped to improve lives must matter more – a person who is already motivated to help others, for instance, needs no further incentive. Causing talented people enjoyment is only uniquely significant to the extent it motivates them to help others more. And the precise extent this is, is by no means obvious – after all, the enjoyment a person derives from (e.g.) increased compensation is subject to dramatically diminishing returns.

But to the extent an increase in quality in life can be used to motivate people to improve the lives of others – shouldn’t it? Why not? It’s entirely possible for a thing to serve simultaneously as an end in itself, and as a means to some additional good thing. Wouldn’t using enjoyment to incentivize helping others lead to a better world overall? Don’t we, ordinarily, expect good choices to be rewarded?

And shouldn’t resources be allocated in the way which leads to the best outcomes – shouldn’t the scalpels be given to the doctors, so that they can heal, and the instruments to the musicians, so they can make music? Shouldn’t paintbrushes go to the best painters? It’s certainly the case that discernible exceptions may arise, and the optimal allocation of resources is ultimately non-obvious (and it certainly doesn’t admit of precise calculations), but where is the contradiction in this? One might disagree with this account (one might even disagree with it on utilitarian terms) - but if the account is incoherent, I simply don’t see how!

Criminal Justice

Winegard then contends that utilitarianism has troubling implications for criminal justice:

Suppose, for instance, that in a country of 350 million, a famous pop singer is credibly accused of domestic abuse. The act causes -100 hedons of suffering to his spouse. If he is not punished, the emotional harm to her continues, subtracting another -100 hedons. But if the crime becomes public, ten million fans each suffer a minor disappointment, say, -.01 hedons, resulting in a total of more than -1000 hedons, surpassing the victim’s suffering. In this case, the consistent act utilitarian would have to conclude that the crime should be concealed and that punishment, if administered at all, should remain secret.

This is another empty bullet. Once again, look at what we are asked to stipulate. Here, the only morally relevant factors considered in the hypothetical are the disappointment of the fans and the suffering of the singer’s wife. We stipulate that there are no other morally relevant consequences. We are to suppose:

that no long-term deterrent effect results from punishing domestic violence;

that declining to punish a domestic abuser enables no future bad behavior (by himself or other celebrities);

that no third parties experience happiness or relief at him being brought to justice;

that his wife misses out on no enjoyment from living the rest of her life without domestic violence, and misses out on bringing no enjoyment to others;

that there is no risk of a massive scandal which erodes the legitimacy of the courts, if a coverup is exposed;

that rehabilitation, for whatever reason, is entirely off the table;

that, if convicted, the singer pays no reparations;

and that all decisionmaking members of law enforcement have certain knowledge of all of the above.

But these considerations, and countless more, are captured by our intuition that, generally, domestic violence is harmful, and it’s good to punish it. I certainly think it is, for the reasons I’ve listed, among others! If we consider a gerrymandered hypothetical case where the vast majority of the considerations which yielded this intuition are stipulated as false (regardless of whether such a case has ever occurred), is it any wonder we draw counterintuitive conclusions about that case?

Average Utilitarianism

Winegard then offers a criticism of average utilitarianism, which someone else can defend, if they like. I don’t care for average utilitarianism, and don’t understand its appeal.

Aggregate Utilitarianism

Then he goes after the aggregation approach:

On the other hand, if the goal is to maximize aggregate utility, we encounter a different conundrum famously articulated by Derek Parfit as the Repugnant Conclusion. The basic idea is this: if total utility is what matters, then we can (almost) always imagine a scenario in which average well-being decreases, but total well-being increases, by adding more people whose lives are barely worth living. For instance, if we have 100 people each enjoying a utility level of 90 out of 100, we could improve the overall total by adding 1,000 people whose lives are just above the threshold of despair. The result is a larger population living more joyless lives, but a bigger total utility score. By this logic, a million people in purgatory are morally preferable to a thousand people in paradise.

I think the “repugnant conclusion” is not nearly as repugnant as it sounds. Notably, Parfit himself did not reject it, and even issued a public statement alongside twenty-eight other ethicists stating that “[t]he fact that an approach to population ethics (an axiology or a social ordering) entails the Repugnant Conclusion is not sufficient to conclude that the approach is inadequate.”

Further, the rhetoric used on this point is needlessly loaded. By definition, these lives are not “joyless.” Nor are they “just above the threshold of despair”; rather, they are just above the threshold of overall unpleasantness. The references to “purgatory” are misleading here as well, as purgatory is not generally a place which is, on balance, worth being in. These lives are, definitionally, worth living. Each person in this world who doesn’t exist, would be better off if they did.

Lastly, the hypothetical picture of a world that the repugnant conclusion paints is highly counterintuitive! It is very, very far from reality! Counterintuitive facts about it might be true as a result!

Winegard extends this point:

Furthermore, by this logic, most of us (at least in affluent societies) have a moral obligation to have as many children as possible, so long as those children would live lives above the threshold of suffering.

This doesn’t follow, actually, just mathematically. Suppose the highest number of children you can feasibly raise is, say, 20. Even if you did this, and all 20 children ended up living net-positive lives, it may well be the case that raising a family with 4 children would have been better, if the average child in the size-4 family is 5x further from net-zero-happiness than the average child in the size-20 family.2

Nor does this imply that people who raise small families, or have no kids at all, deserve blame or condemnation. Recall that, as Winegard points out, utilitarians strive to distribute censure and punishment only when doing so results in a foreseeably net-positive outcome. Even if one supposes that it’s generally better to have a large family (a question on which many utilitarians are undecided, and, in any case, an extremely fact-dependent one), there’s no good reason to suspect that condemning small families will, in the long term, make them larger or happier.

Lastly, Winegard points to a very real measurement problem when it comes to experiential states:

A final problem for utilitarianism is that mental states may be incommensurable and unpredictable, making comparisons across time difficult, perhaps even impossible.

This is certainly the case, and, if anything, it is a very salient explanation for why the philosophy of ethics has remained as fraught as it has for millennia. It is simply hard to figure out the facts concerning enjoyment and suffering. We do not always know what we enjoy, or what causes us suffering, or the relative amounts of each, and as for others, we can rely only on inferences from their reports and behaviors.

It is simply a fact that when we aim at enjoyment and suffering, we are generally aiming at targets which are at once hidden, and moving. These are hard facts to figure out. But if they matter, they matter. We cannot feasibly discard an ethical framework just because it is tricky – perhaps we just live in a tricky world! Rather, we should be doing what (I’d argue) we already do – developing general principles in a society based on the reasonably foreseeable outcomes of defined categories of conduct. It is impossible to measure and state with perfect certainty that any given instance of theft, dishonesty, or even murder, ultimately pans out in more good consequences than bad, on an infinite timescale. But we are nevertheless able to say that murders reliably and foreseeably seem to cause more bad consequences than good ones, and, all else being equal, this is a reason not to do them and to try to prevent others from doing it.

Conclusion

This is not to say that utilitarianism in its present form is a complete moral science. Not all formulations work, and even the best conceptions doubtless need tweaking. But all told, at the end of the day, I think that utilitarianism is at once the most practical, intuitive, and decent ethical framework on offer.

If utilitarianism is wrong, one must admit, it is at least wrong in the right direction. Utilitarians have, historically, been on the cutting edge of moral progress. Bentham was one of the earliest thinkers to offer a serious defense of gay rights. Mill was an early and outspoken feminist. Singer, too, will likely go down in history as a moral pioneer, especially regarding animal rights. I don’t expect Winegard’s article - well-written though it is - to prevent this.

Doubtless there is someone who has come before me and already coined a term for this, but after a brief search, I found none - if anyone can point me in the right direction, I will be in their debt.

This is then complicated by a number of other moving pieces, such as resource scarcity, or the fact that the children will go on to variously improve and worsen the lives of others in the world - which would further solidify the case against there being an obvious moral imperative in either direction.

I very much enjoyed this, and you made some important and plausible arguments. If I get some time, I would like to respond in more detail. For now, I concede that the point about purgatory was excessively rhetorical. I would add however that my intuition tells me that 100 flourishing people (100/100) are better than 1000 people who barely want to remain alive (5.1/100). On the other hand, I don't know that adding up utility across people makes metaphysical sense, though it is probably useful--perhaps indispensable--for public policy.

Bo

Let us compare here on the one hand the most common understanding, gifted with very limited intellectual capacities with on the other hand a highly intellectual understanding which is capable of foreseeing lots of possible consequences of his actions (maybe he’s a scholar in ethics). When they are both presented with a moral issue in which they have to decide which action is the morally right thing to do, the only difference between the two will be that the first has less oversight of all the possible consequences of his action. The second will have more oversight of possible consequences of his action but the moral principle that determines their will in taking action is exactly the same in both cases. Moreover while the scholar might have the impression that he’s better capable of foreseeing more consequences and thus capable of a better moral decision, he must admit he can’t foresee all the consequences of his action as time will progress and in the end his action is as potentially disastrous (or even more disastrous) for human kind as the action of the common man.

When looking at human history it could even be said that most of mankind’s self inflicted disasters are caused by those who had the impression to foresee the most consequence of their actions and acted accordingly to an idea they thought was possible to complete with certainty in this world.

This of course doesn’t mean that we should not consider the consequences of our action, on the contrary. We ought to do so each in our own capacity but it is obvious that the more we foresee possible consequences, the more indeed we see a potential increase in possibly good outcome, but at the same time a potential increase in possible bad outcome and also an increase in uncertainty of outcome.