“I am a man of fixed and unbending principles, the first of which is to be flexible at all times.”

- Everett Dirksen, The Education of a Senator

A recent article by Bentham’s Bulldog advocates widespread illegality, on entirely sensible terms:

If enforcing some law would violate rights and lead to bad consequences, you shouldn’t enforce it!

He cites three examples in which this principle might be applied to legal professionals. On his account, an attorney who correctly believes their client is guilty of a heinous crime should not dutifully represent the client and get him acquitted. A Supreme Court justice who correctly believes an unconstitutional law is good, should write a dishonest opinion which permits the law. A police officer who correctly believes that some law is unjust, should disregard their duty to enforce it.

There are many simple and bad objections to BB’s argument – several of which BB addresses and, by my lights, effectively dismembers. These fail because this argument is very solid on the fundamentals – as a universal principle, a person should not cause unnecessary harm, and if they correctly believe that following some law or rule would cause unnecessary harm, they shouldn’t do it. Further, a thing being legal, in and of itself, doesn’t do much to make harm it causes necessary. Some rules do suck. Enforcing a law purely for enforcement’s sake is pointless. I am persuaded of this.

Even still, as an attorney myself, I want to offer some explanation on behalf of the legal profession – not of why this argument is rejected, but rather, of why it seems to be. I would wager that BB’s argument is far less controversial among legal professionals than his article anticipates. But this argument, taken at face value, cashes out in unexpected ways. This principle is broadly accepted – but only ever quietly – and virtually never acted upon. Most people with any real power, if asked, will loudly disagree. The vast majority of legal professionals adhere to all applicable rules and laws as a matter of course, and most make minimal exceptions, if any, across the course of their careers. Those who hold themselves above the law, even on matters of moral principle, are condemned and punished. Why?

First, we must consider what contexts exactly Bentham’s argument applies to. These are edge cases. On the vast majority of matters, the laws are by and large sensible, and where they aren’t, it’s difficult to reliably plot an obviously preferable alternative course. Real, honest-to-goodness moral dilemmas are rare.

Second, of course, there are prudential concerns. Even if one correctly believes that they have uncovered an exceptional case in which rulebreaking leads to foreseeably good long-term outcomes, rulebreakers face steep penalties: they expose themselves to sanctions, loss of their job, liability, and public disgrace. These make it easy to be uncertain. We are only assessing a narrow slice of cases where a person is somehow certain and correct that they can break rules without getting caught – or certain and correct that it is so important to do so, that the punishment is worthwhile.

Third, there are matters of epistemic humility. In my experience, a person’s likelihood of being correct is inversely proportional to their degree of certainty – the confident people tend to be the wrongest, and the most generally correct people are almost always reasonable enough to admit they may have erred. Most lawyers, myself included, are of this sort. So our slice is further narrowed to the rare few who are confident that rulebreaking is worthwhile, who are correct about this as a matter of fact, and who are correctly undeterred by the prospect of punishment.

There is a technical term for people of this sort – the “hotshot.”

Introduction to Hotshot Theory

As a general principle, people are systematically and constitutionally incapable of reliably identifying themselves as hotshots, and the vast majority of self-considered hotshots are dangerous losers.

But hotshots do exist. Hotshot theory models many situations within the legal profession, but it is much more broadly applicable. Hotshot theory applies to any set of rules – from the US Constitution, to the rules about who refills the coffee pot in the break room, to the rules parents enforce regarding bedtime for young children.

A hotshot is not a type of person, exactly – rather, it is a specific position that a person can find themselves in with respect to a set of rules. Hotshots think they are above the rules, and the bitch of it is, they are correct. However – and this is why the article is titled “a modest defense of injustice” – in many cases, hotshots still should be punished.

A toy example, to illustrate. Consider a police department with two officers – Officer Wiseass and Officer Dumbass, who are overseen by Police Chief Jones. All three are rational decision-makers who believe they should refrain from making choices that will foreseeably cause unnecessary harm. Officers Wiseass and Dumbass are tasked with enforcing a small town’s laws. The vast majority of these laws are both just and uncontroversial.

However, two laws in this town are controversial: Law A and Law B. Law A is unjust – it bans some sort of harmless conduct, like speaking French. Law B is just – it bans harmful conduct, like child marriage, or failing to subscribe to the Blog of Gumphus.

Officer Wiseass and Chief Jones both correctly disapprove of Law A. Officer Dumbass incorrectly disapproves of Law B. If Officer Wiseass breaks the rules, and allows residents of the village to violate Law A with impunity, the village is better off. This is optimal, perhaps – until Officer Dumbass finds out. The only thing keeping Officer Dumbass from letting terrible people off the hook for violating Law B, is his respect for the rules. The more the principle “enforce the laws” erodes, the less likely Officer Dumbass is to enforce Law B. And if the department has twenty other Officer Dumbasses, they will all begin picking and choosing which laws to enforce. This is unacceptable – and Chief Jones knows this.

So, if Officer Wiseass gets caught breaking the rules, Chief Jones must loudly and publicly say, “what Officer Wiseass did was unacceptable, he has disgraced himself, he is suspended,” and so on. Officer Wiseass’s conduct must be criticized in all public channels, lest any of the Officer Dumbasses get the wrong idea. Officer Wiseass must be punished, unjustly – because Officer Dumbass exists.

Conclusion

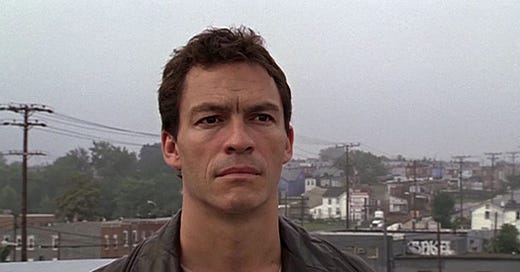

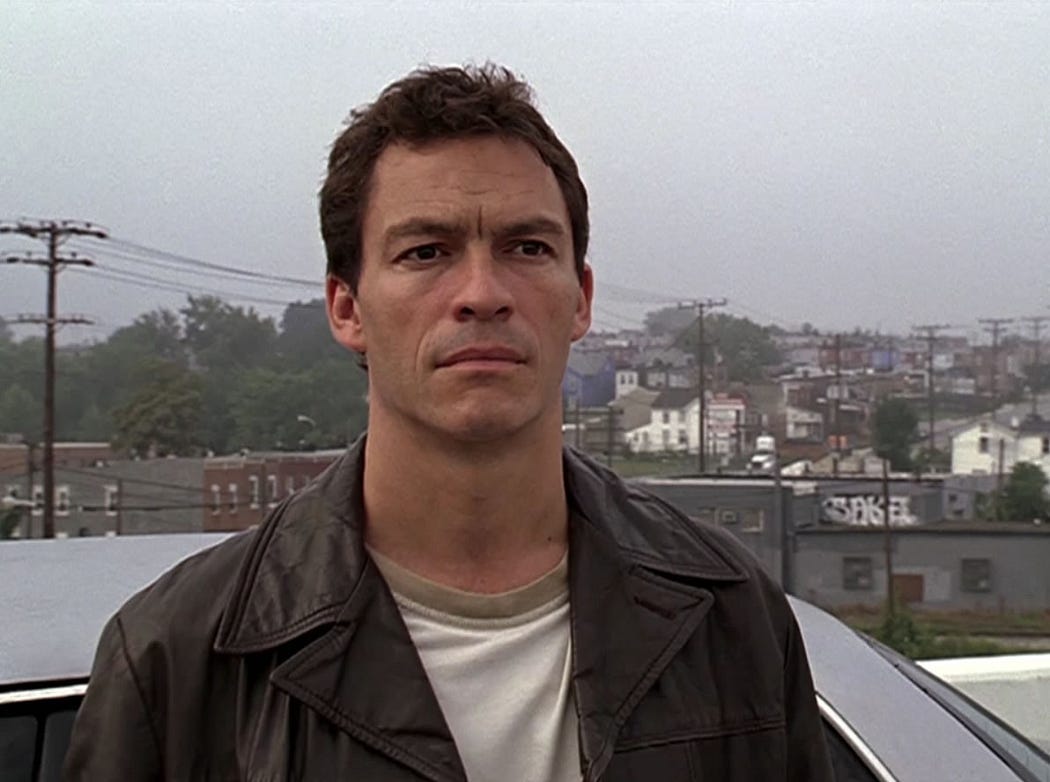

This is a simple case – but many of the real-world challenges of leadership and governance are really just complex applications of hotshot theory. If Chief Jones lets Wiseass off the hook, Officer Dumbass will become bitter and rebellious. If Chief Jones punishes Wiseass too harshly for conduct they both know is harmless, Officer Wiseass will become bitter and rebellious. A good leader must be able to tell the Wiseasses from the Dumbasses, and treat them both appropriately. A person might be a Wiseass with respect to one rule but a Dumbass with respect to another. On an issue where everyone is a Wiseass, there is no need for rules at all. On an issue where everyone is a Dumbass, there is no one to write the rules in the first place. The better a set of rules is, the fewer hotshots it will generate, and a terrible set of rules might make great swathes of the population into hotshots. A good institution may eventually guide its Wiseasses into a position where they can shape the rules - but only after ensuring the Wiseass appreciates the value of the rules, imperfect though they are, and understands the basic precepts of hotshot theory. The stories we tell in a society feature hotshots prominently, and, by doing so, can teach us about the rules we live by.

By my lights, arguing that it is possible as a general principle for people to correctly consider themselves hotshots, while true, has minimal upside. People who are in fact hotshots do not need persuaded of this. It is futile to give a real hotshot permission to be a hotshot – the whole point of being a hotshot is that they do not need permission. On the other hand, the Dumbasses of the world – especially the Nietzsche-worshipping ones, who want permission to break the rules, and aren’t bright enough to realize this makes no sense – are emboldened by pro-hotshot rhetoric.

To conclude: hotshots are real, rare, impossible to reliably identify, extremely important to understand, and of course, we should all agree and say out loud that hotshottery is one hundred percent unacceptable. Also, you aren’t one. And neither am I!